Author: Anupama Nallari

We often look at what’s wrong in slums and informal settlements. Here, I draw attention instead to one of their assets: the common space outside people’s homes. I explore its importance for children’s play and development, while unpacking the fluidity and changing nature of these spaces. And as increasing competition for their use leaves less and less room for children’s play, I suggest recommendations for how we can protect and co-create these valuable outside spaces for children, their caregivers and future generations.

Common space outside homes: a (disappearing) asset

Between 2010 and 2012, I visited four informal settlements and four redeveloped settlements[i] in Mumbai and Bengaluru in India, to examine the meaning and importance of common spaces for the women and children living there.[ii] [iii] I discovered that caregivers highly value the space outside their homes. The residents I spoke to said they used these spaces for many of their daily household chores while keeping an eye on their children. They also said that the space outside their homes not only supports children’s play. It keeps communal life and traditions alive, extends indoor spaces, nurtures family bonds and provides a cooler space during hot summer months. Young children can see their caregivers at work while they play with their siblings, parents and grandparents, friends and neighbours. They can listen to their conversations and learn from them, while at the same time developing their own agency.[iv]

All of these factors enable communities to thrive and build resilience. But despite this, the value of outside common space is often overlooked by both residents and professionals. Their ‘informal’ nature often leads to their demise. In many redevelopment and upgrading efforts, children’s play is often supported by a ‘build-a-playground’ approach – rather than improving and protecting settings that already support children’s play.

Outside space for children: weaving play into everyday life

Common spaces are shared spaces. They can be private, semi-private or semi-public. In redeveloped settlements, these are typically balconies, corridors, stairways, courtyards, community halls, rooftops, religious spaces, parking spaces and entrance ways. In informal settlements, they are typically lanes, streets, shopfronts, cemeteries, abandoned lots, garbage dumps, vacant lands – and space in front of people’s homes.

The outside spaces most valued by residents I spoke to were those that were safe and allowed for a range of activities. During the day, these spaces were often bustling. Household chores, microenterprises and childcare were layered and woven into everyday communal life. In all four informal settlements, I found that young children (aged 1 to 5 years) often played just outside their homes. Here, they could be easily watched over by their caregivers as they went about their daily chores.[v] Cooking, washing and food preparation all took place outside the home, as space inside was too constrained and/or lacked ventilation.

Children engaging in various forms of play outside their homes in informal settlements © Anupama Nallari

I saw that passers-by often stopped to chat and play with young children. While I spoke with residents, their children played with pots and pans, coconut shells, water, sand, leaves and twigs, as well as toys. I observed young children playing peek-a-boo with their caregivers as they were folding laundry or chucking vegetable peelings into water to watch them float. I saw children banging on metal pots or leaping up to reach a toy held high by a sibling.

Such play has a range of benefits for children. It helps them to make friends, to regulate their emotions, learn about their physical environment and push their physical limits. It also aids their sensory development.[vi] I spoke to one young mother who shared a semi-covered open space with her next-door relatives. She said,

Our family and his brother’s family who live next to us, we all use this area many times. We store water here. Children play here. After eating, they come and sit here. I leave my children here when I dry clothes outside or cook outside in the open area. We sit with friends and chat here. We have some breathing place here. It really helps to have this place, because when I go out and the children come home, they can be here.

Her seven-year-old daughter added:

I play here. Sometimes with water and mud. Then we fight with each other. We play god-god here, and I play with my dolls and toys. My brother studies here. We eat here. We use it to sleep, play and eat. We like this place.

Adolescent girls also found the space outside their homes to be a safe outdoor haven. Here, they could chat with their friends or read without being harassed. School-aged children had a wider range of play spaces away from home. But on weekdays, when they had to balance school, homework and household chores, they often used these proximate spaces for playing board games, hopscotch, ball games and five stones (a traditional game popular with children in India).

How diminishing space affects young children’s health and development

This amicable sharing of space, however, is often short lived. Home extensions like small shopfronts, rooms, toilets or even additional houses can take over these spaces. This leads to overcrowding and aggressive claims over the little available space left for children’s play. For many of the families I spoke to, as the space outside their homes diminished, household chores gradually moved indoors.

The consequence of this was a higher demand on indoor space. Caregivers found they had to restrict young children’s movements to keep them ‘out of the way’. This double burden of managing caregiving and getting through daily chores indoors can heighten caregiver’s stress levels and lead to increased violence towards children.[vii]

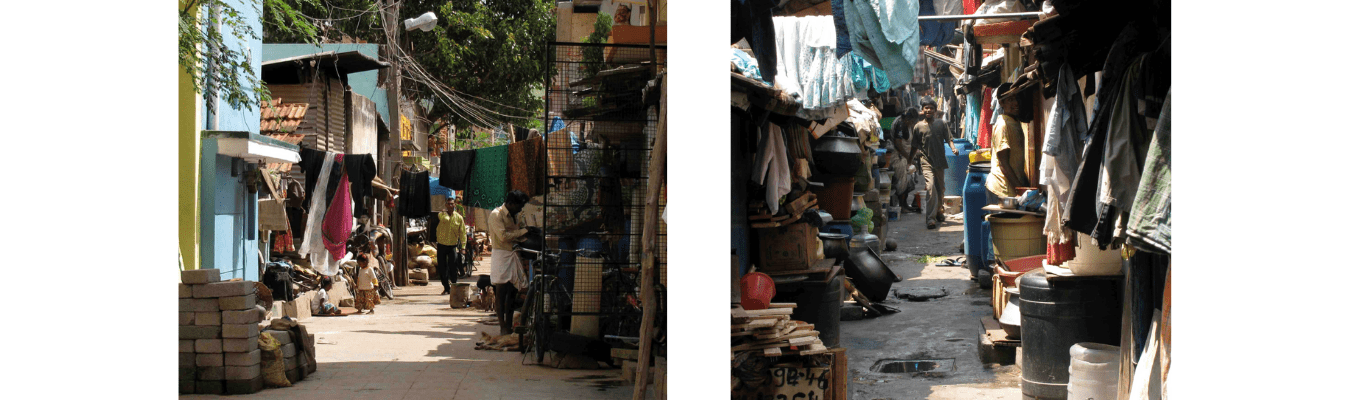

The photo on the left shows a settlement with relatively wide streets between homes that afford play opportunities for children. The photo on the right is a street in a very dense settlement. The streets have shrunk over time and space is highly contested © Anupama Nallari

Increasing densities and inadequate services have also brought closer to home garbage, waste and standing water. These pose a range of threats to children’s health and safety. I found that children gravitated towards these spaces because of their natural propensity to play. But this caused much angst amongst their caregivers, who were concerned with children’s safety. One elderly grandmother pointed to her youngest granddaughter and said,

This younger one is a real ‘badmash’ [naughty girl] … She keeps running outside to play here and there and someone or the other will be shouting at her to come back into the house. She says she wants to play… What can I say to her? She plays with other small children in the area. She will play with the mud outside, then with the garbage lying there… What to do? She is still a child.

In search of better outside space

Multi-storey redevelopments and poorly designed outside space

Some families I spoke to had transitioned to multi-storey redeveloped housing. Their children continued to play outside their new homes. But their play was less varied and less frequent compared to informal settlements because of poorly designed spaces and safety concerns.

One young mother pointed to the wide gaps in the balcony railing outside her home. She complained that on more than one occasion, her toddler had got his head stuck when he peered down to observe life on streets below. Some caregivers were terrified that their children would fall to their deaths and so preferred to keep them indoors. Internal corridors were often dark and empty and offered little opportunity for the kinds of play that keep children immersed for long periods. Instead, children often ran up and down these corridors, raising the ire of adults.

In redeveloped settlements the spaces outside homes also held ‘class’ notions. Some residents in multi-storey dwellings felt that children playing or adults engaging in activities such as sorting grains or chopping vegetables in corridor spaces was ‘what you did in slums’. Many of the women I spoke to worked as domestic helpers. They aspired to be more like their middle-class employers and lead a ‘better life’. This had led them to shun these outdoor spaces and even police others from using them as well.

The photo on the left shows a multistorey redeveloped settlement with poorly lit internal corridors. The photo on the right shows low-rise redeveloped housing with more vibrant and useful space outside homes © Anupama Nallari

Community-led low-rise redevelopment: better outside space

Compared to other redeveloped settlements in my study, one low-rise housing redevelopment stood apart for its careful attention to spaces adjoining homes. This settlement had been planned and built with intense community engagement and this was reflected in the built environment. Each house had a small veranda and opened onto a shared courtyard. One resident who had recently purchased a home described excitedly how she uses and values the space:

I also sit here because it is cool. I cut vegetables, wash clothes and read the paper also… All that, I do here. I sit and talk with my neighbours all the time… I have put the plants here. I love plants. This place outside our house is very important… I do most of my work here. To tell you the truth, we bought this place after seeing this space outside the house. There is a place to sit outside and it feels a little free.

Creating better outside space for children

Given the importance of outdoor common spaces to children’s health and development, what can be done to protect, co-create and maximise play opportunities for children close to their homes in existing and redeveloped settlements?

- Regularise: Common space outside homes needs to be both legitimate and safe. An important first step is for governments and local authorities to recognise slums and informal settlements as legitimate forms of housing in the city. Residents need secure housing rights as well as access to basic services.

- Funding: Governments should allocate specific funds for developing common spaces in both existing and redeveloped settlements. These funds can also be raised within communities at the block level if there is collective agreement on the need to improve these spaces. Co-funding can increase community ownership and management of these spaces and increase their longevity.

- Advocate: Children’s organisations as well as grassroots organisations should advocate to community members the importance of children’s play for their well-being and development, using locally relevant examples of play. They should explain and create awareness about how play is integral to brain development as well as social and physical development.

- Map: Grassroots organisations, children’s organisations and other NGOs as well as urban planners should engage children and caregivers in a participatory mapping exercises of settings where children play. Record in detail how play unfolds and the actions and moments that prompt play. Discuss their preferences and values for these places as well as risks and opportunities. Use this evidence to advocate for common space outside homes in existing and redeveloped settlements.

- Protect: Grassroots organisations, children’s organisations and urban authorities should use community engagement forums to discuss how these spaces can be protected. Identify concrete possibilities such as shared ownership agreements or common land-pooling strategies to retain/reinvigorate these spaces in upgrading and re-blocking settlements.

- Plan and build: Parties leading upgrading and redevelopment efforts should conduct participatory design workshops with children, caregivers and other stakeholders to explore and co-create innovative and low-cost options for spaces outside homes in settlement upgrading and redevelopment projects. The Baan Mankong Programme in Thailand[viii] as well as the Asian Coalition for Community Action (ACCA) programme[ix] are both great examples of how common spaces have been supported in such projects. Likeminded groups built their houses in clusters surrounding common areas where trees can be planted and common activities take place, with roads on the periphery.[x]

- Promote and maintain: Grassroots organisations, settlement leaders and children’s organisations should organise annual settlement-wide competitions for spurring residents to develop the space outside their homes to its fullest potential – and to maintain these spaces long term. Engage students across disciplines such as planning, design, architecture, community development and child development to work with residents to create useful, workable and low-cost interventions. Celebrating these spaces and giving them the importance they deserve can also change class-based notions around such spaces.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to everyone at the Society for the Promotion of Area Resource Centers (SPARC) and Mahila Milan at Mumbai and Bengaluru for enabling this research as well as the research participants for their warmth, patience and invaluable insights and generosity. I would also like to thank Sarah Sabry, Cecilia Vaca Jones and Sara Candiracci for their valuable inputs on earlier versions of this blog and Holly Ashley for her amazing editorial support.

About the author

Anupama Nallari is an independent research consultant who works at the intersections of child well-being and urbanisation, poverty, early childhood settings and public space. Anupama.nallari@gmail.com

Endnotes

[i] Redeveloped settlements are settlements built through government or other funds to rehouse residents in slums, where residents most often have access to secure tenure and basic services.

[ii] Nallari, A (2014) The meaning, experience, and value of ‘common space’ for women and children in urban poor settlements in India. PhD thesis. City University of New York. https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/80

[iii] As part of this research, I interviewed 84 caregivers and their children (aged 5–18) across the eight settlements, conducted adult-led tours comprising 4–6 adults (mostly women) and child-led tours comprising 6–8 children. For more details on methodology please see Nallari (2014).

[iv] Rogoff, B (2003) The cultural nature of human development. Oxford University Press. https://bit.ly/3layoJX

[v] For more evidence, please refer to this recent study which found children in some informal settlements in India most often played outside their homes: Krishnamurthy, S and Özlemnur, A (2020) Supporting urban childhoods: observations on caregiver use of public spaces from Pune (IN) and Istanbul (TR). Bernard van Leer Foundation. https://bit.ly/3f0ZnU3

[vi] Lester, S and Russell, W (2010) Children’s right to play: an examination of the importance of play in the lives of children worldwide. Bernard van Leer Foundation. https://bit.ly/3rElZ1P

[vii] Bartlett, S (2017) Children and the geography of violence: why space and place matter. Routledge.

[viii] Boonyabancha, S (2005) Baan Mankong: going to scale with “slum” and squatter upgrading in Thailand. Environment and Urbanization 17(1). https://bit.ly/2VhnsPs

[ix] See some of the small upgrading projects in the ACCA programme for ways through which spaces near homes and within the community can be developed for children and other community members. An independent evaluation of the ACCA programme also sheds light on the importance of these projects for community resilience, long-term development, building partnerships and legitimising capacities of communities. See: World Bank (2013) A review of the Asian Coalition for Community Action approach to slum upgrading. East Asia and Pacific Sustainable Infrastructure Unit, World Bank. www.achr.net/upload/downloads/file_16032014122116.pdf

[x] Boonyabancha, S (2009) Land for housing the poor—by the poor: experiences from the Baan Mankong Nationwide Slum Upgrading Programme in Thailand. Environment and Urbanization 21(2). https://bit.ly/3ygFJve

Note: This article presents the views of the author featured and does not necessarily represent the views of Global Alliance – Cities 4 Children as a whole

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.