Author: Tim Gill

My last blog made the case for child-friendly urban planning as a catalyst for healthier, more sustainable cities. It set out a two-dimensional framework highlighting the role of mobility on the one hand, and a wide choice of things to do (crucially including places to play) on the other. This blog looks in more detail at the physical and spatial features that make neighbourhoods work well for children.

Talk to any caregiver for ideas about how their neighbourhood could be more child-friendly, and playgrounds are likely to be top of the list. The public playground emerged as a model during the rapid industrialisation and urbanisation of cities in North America and Europe. It has now spread worldwide, but still tends to have a similar design template: a patch of flat ground (often fenced-off) with pieces of play furniture (often brightly coloured) and perhaps some kind of soft surfacing.

The problem with playgrounds

There is no denying that urban children and caregivers value public play areas as places of refuge and respite, and as neighbourhood meeting points. But on their own, playgrounds will never be enough to make cities truly work for children.

One problem is that playground designs rarely match up to children’s appetite for fun, with teenagers and more adventurous children especially poorly served. An overemphasis on gross motor activity downplays or ignores the richness of children’s play and the varied interests and abilities of different children.

A more serious drawback is that playgrounds can reinforce children’s exclusion from the rest of the public realm. Given the chance, children can and will play almost anywhere. Yet in many neighbourhoods, playgrounds end up being the only places where their presence is tolerated. (The radical town planner Colin Ward in his seminal book The Child in the City provocatively suggested that “the failure of an urban environment can be measured in direct proportion to the number of playgrounds”.)

All too often, playgrounds are token gestures, used like sticking plasters in an urban fabric that is otherwise highly hostile to children. This conclusion may sound overly harsh, but it is supported by two systematic studies of neighbourhood planning and outdoor play, which suggest that traffic levels and street designs and layouts have a greater influence on the actual time children spend playing outdoors than the presence or distribution of playgrounds.

Public playground in Bogotá. Credit: Tim Gill

A different approach

The flaws in what could be called the ‘playground formula’ point to a different approach to making places more child-friendly. It starts with the neighbourhood – not an individual space – as the unit of analysis. It sees walking and cycling networks as essential ingredients: the threads that stitch neighbourhoods together for children. And it aims to weave a wide range of playful, sociable offers and invitations into a welcoming, green, multifunctional public realm.

Ideally, these offers and invitations begin right outside families’ front doors (where space for play is especially valuable for caregivers with young children). And they extend into all the spaces and places where families spend their daily lives. Streets, courtyards, public squares, shopping areas, schoolyards, urban green spaces and paths and alleys can all be opened up for play and socialising.

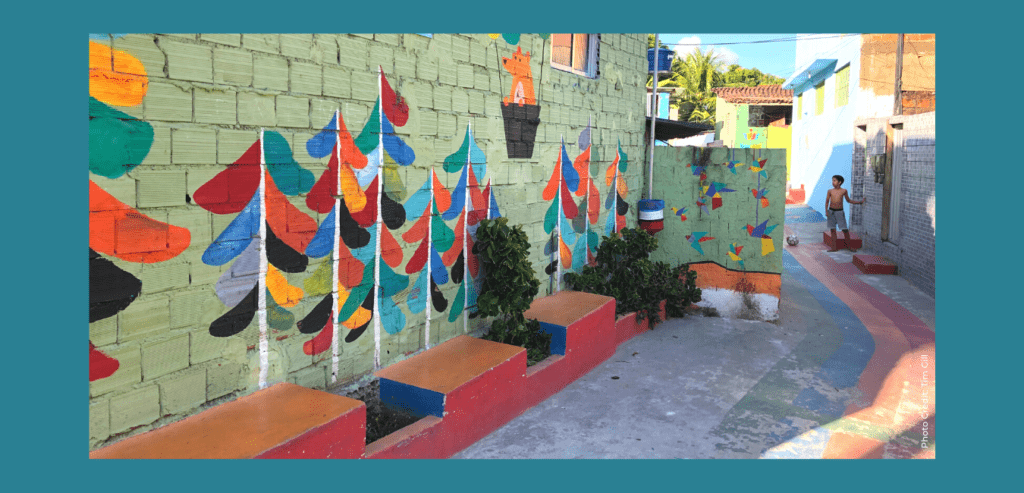

Street reclaiming scheme, Fortaleza, Brazil. Credit: Paulo Winz / NACTO-GDCI

In some locations, all that may be needed is some seating and a spring-clean. One Recife favela saw dramatic increases in outdoor play after completing a low-cost scheme to tidy up paths and watercourses and repaint alleyways and streets. In others, more radical measures may be called for, such as opening up school grounds for public use, limiting motor traffic, or introducing playful structures to civic spaces to enhance the play offer and – just as important – give a green light for children and caregivers.

In dense urban residential areas, every square metre of available public space has to work hard. While space for play should be in the mix, carving out segregated play areas makes little sense. The truth is that different population groups often have patterns of daily outdoor use that overlap well. Mornings see early risers venturing outside, followed a little later by caregivers with young children, and perhaps seniors. Lunchtimes are for adults living or working nearby, with schoolchildren appearing in the afternoon, followed by teens and night owls later on. With good informal oversight, the right management and creative design features, there is no reason why the same space cannot be safe, welcoming and stimulating for all these groups.

Trees and natural places are universally valued by urban dwellers. What is more, while spending time in natural spaces is good for everyone, it is especially important for urban children: even more so in disadvantaged neighbourhoods. The climate emergency means many cities will need to increase their tree cover and green infrastructure. If urban resilience programmes also lead to more playful, sociable spaces, the result will be a win-win for children and the planet.

Public space with play platform, Taipei. Credit: Ching Tsai, Taiwan Parks & Playgrounds for Children by Children

My book Urban Playground proposes a set of ten strategic indicators that aim to capture what child-friendly places look and feel like from a child’s point of view. They are short, clear, measurable and reasonably comprehensive. While the details (and age ranges) will vary in different contexts and cultures, they form a sound starting point for shaping policies and programmes.

Ten strategic indicators for a child-friendly neighbourhood

- I walk to school/local shops without an adult (from age 8).

- I cycle to school/local shops without an adult (from age 8).

- I go outside and play within sight of my home (up to age 11).

- I feel welcome and safe outside, during the day and after dark.

- I have access to natural green space in my neighbourhood.

- I have access to an outdoor place in my neighbourhood that is peaceful and quiet.

- My neighbourhood has lots of trees.

- I have access to a choice of outdoor places in my neighbourhood where I can meet and spend time with friends and there are fun things for us to do, including places where I can test myself and take some risks.

- I have access to an outdoor place in my neighbourhood where my extended family and friends can have a picnic.

- I travel from my own neighbourhood to downtown areas on foot, by bike or by public transport (from age 11).

The big picture is that city leaders around the world are taking on the challenge of tackling car-dominance, creating inclusive public space and greening the urban environment. These moves to humanize cities are inherently child-friendly in themselves. They can have an even bigger impact if they adopt a neighbourhood-wide ‘children’s lens’. The results will not only improve the lives of urban children and families. They will also help to build the political case for long-term, structural improvement to the built fabric of cities.

This blog is part two of a series by play expert Tim Gill, founder of Rethinking Childhood and author of bestselling RIBA book Urban Playground: How Child-Friendly Planning and Design Can Save Cities.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. When re-sharing this content please ensure accreditation by adding the following sentence: ‘This blog was first published by the Global Alliance – Cities 4 Children (www.cities4children.org/blog)’