Author: Tim Gill

In his latest blog Tim Gill describes why adult catalysts are necessary for enabling child-friendly urban environments and argues that municipal champions who understand children’s views and needs have a key role in building ambitious programmes.

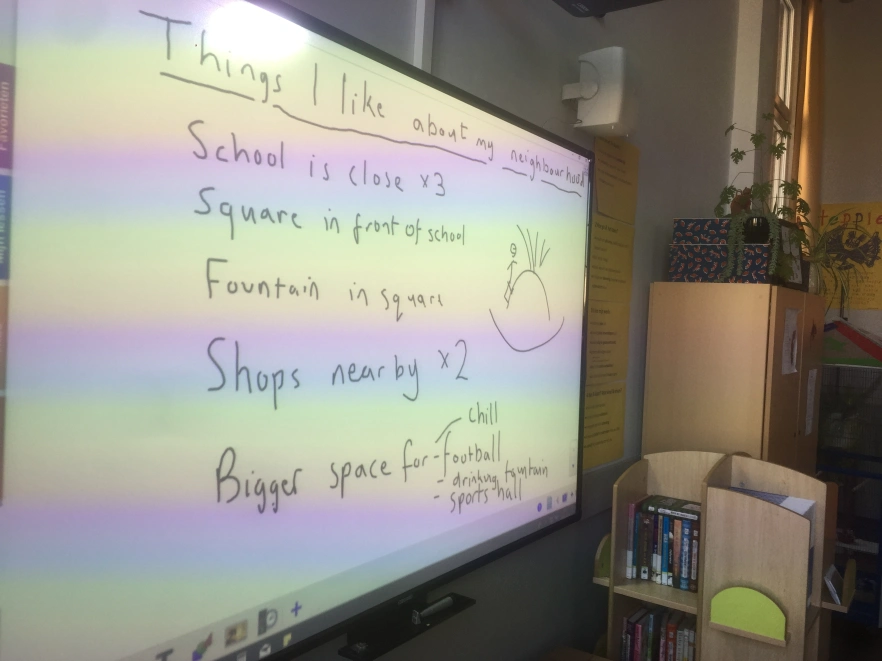

Whenever children pretty much anywhere in the world are asked what they like and dislike about where they live, their answers are almost always the same. In spatial terms, they like choice and variety in places to play and socialise, including contact with nature. They like to be able to get around their neighbourhoods easily and safely on foot or by bike. And they dislike traffic, pollution and litter and environmental neglect.

What is more, outdoor play and mobility are unquestionably good for children’s health, well-being and development. This convergence of what children say and what is good for children underscores the substantive framework and vision set out in Urban Playground and summarised in the first two blogs in this series.

Children’s views about their Antwerp neighbourhood © Tim Gill

Despite this – and in direct contravention of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child – the vast majority of urban planning decisions take no account of their impact on children, and make no effort to seek their views.

This is despite the fact that poor urban planning is harming children the world over. Poor basic infrastructure, traffic danger, and air and noise pollution are directly causing the deaths of hundreds of thousands each year, and worsening the lives of millions. Children in poor neighbourhoods and households, especially in the Global South, are hardest hit.

Children’s participation has little impact on urban decision-making

Given the stark contrast between children’s views and concerns about cities, and the harmful impact of urban planning in most cities, it is no surprise that children’s direct participation in urban decision-making has been put forward as a response. However, an objective look at the evidence base for the impact of children’s participation reveals some depressing findings.

Several comprehensive reviews, drawing on studies in high, middle and low income contexts over several decades, have shown that on the rare occasions when municipalities have sought out children’s views, the results have had a limited impact on neighbourhoods.

Exemplary schemes on individual sites – playground or schoolyard refurbishments, for example – are not hard to find. But it is rare to come across initiatives with any wider influence on the features of neighbourhoods that would truly shape how well (or not) they work for children. All too often, projects are idle wheels that fail to engage with cogs elsewhere in the system (the civic engagement initiative whose write-up sits unused on a shelf).

Alternatively, they are tokenistic activities that lead only to cosmetic changes (the colourful artwork on the side of a playground wall). It is no wonder that two leading academic authors writing in 2017 have described progress on children’s participation in urban decision-making as glacially slow.

Despite the challenges, introducing children’s voices into urban decision-making can have a dramatic impact, as young climate activists and youth movements the world over have shown. Their views carry a moral weight that cuts through the noise, forces us to focus on the long term, and exposes unhelpful adult vested interests.

However, it should not be children’s job to push for change, far less to come up with solutions. As Roger Hart – the godfather of children’s participatory planning – has argued, children’s everyday experiences of urban life need to be more central.

Need for adult catalysts to advocate for child-responsive urban planning

In the light of all this, children’s participation needs to be reappraised. It is still important, which is why we should celebrate countries like Scotland and Sweden joining Wales and Norway in adopting supportive, rights-based national policy.

But when it comes to the large-scale urban transformation that is needed, history tells us that the question ‘how do we involve children in shaping cities?’ is rarely a powerful catalyst. There is a prior question that needs to be asked: how do we get city leaders to care about children?

Reaching and influencing those in positions of power is particularly hard for child advocates, given the near-total exclusion of children from the formal workings of government. Activists , parents’ groups and campaigning bodies are all potential movers and shakers. However, [bctt tweet=”having visited and studied the activities of some of the cities that have put serious resources into making their built fabric more child-friendly, it is clear to me that the key change agent is often a well-placed municipal officer” username=”cities4children”]. Someone with both knowledge and know-how about children’s urban lives, and the ability to influence colleagues in charge of key local government functions such as transport and land use planning.

In the light of this, the 2018 revision of UNICEF’s longstanding and far-reaching Child-Friendly Cities Initiative is an encouraging development: specifically, the introduction of substantive outcomes on planning, play and independent mobility as part of its comprehensive, rights-based municipal change agenda.

Just as significant as policy change is the emergence of international municipal leadership programmes. Two front-runners are the Urban95 Academy delivered by the London School of Economics, and the Global Designing Cities Initiative’s Streets for Kids Leadership Accelerator.

The Urban95 Academy residential in London brought together some 30 municipal officers and local politicians from around the world ©Catarina Heeckt Photography

In May this year, as part of the first Urban95 Academy cohort, I had the pleasure of leading a walking tour of a major public space improvement programme in a formerly run-down part of London with 30 or so public servants from around the world. The group included architects, planning officers, transportation professionals and mayors, and they came from Europe, Africa, the Middle East, North and South America and the Asia-Pacific region.

It is too soon to gauge the long-term impact of programmes like these. But my hunch is that [bctt tweet=”if we are to see change at the scale that is needed, it will be through recruiting, nurturing and supporting municipal children’s champions: people who can speak children’s truths to the grown-ups who hold the power.” username=”cities4children”]

This blog is part three of a series by play expert Tim Gill, founder of Rethinking Childhood and author of bestselling RIBA book Urban Playground: How Child-Friendly Planning and Design Can Save Cities.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. When re-sharing this content please ensure accreditation by adding the following sentence: ‘This blog was first published by the Global Alliance – Cities 4 Children (www.cities4children.org/blog)’