Author: Richard Clarke

‘Nothing seems to change until suddenly it does,’ writes Duncan Green in his book How Change Happens. The exponential growth of school streets over the past five years powerfully illustrates how urban change can sometimes be non-linear and transformational.

What are school streets?

School streets are vehicle-free areas outside schools (or vehicles have severely restricted access). These are normally activated at the start and end of the school day for a short period of time to enable children’s safe and active journeys to school. Some school streets are permanently closed to cars

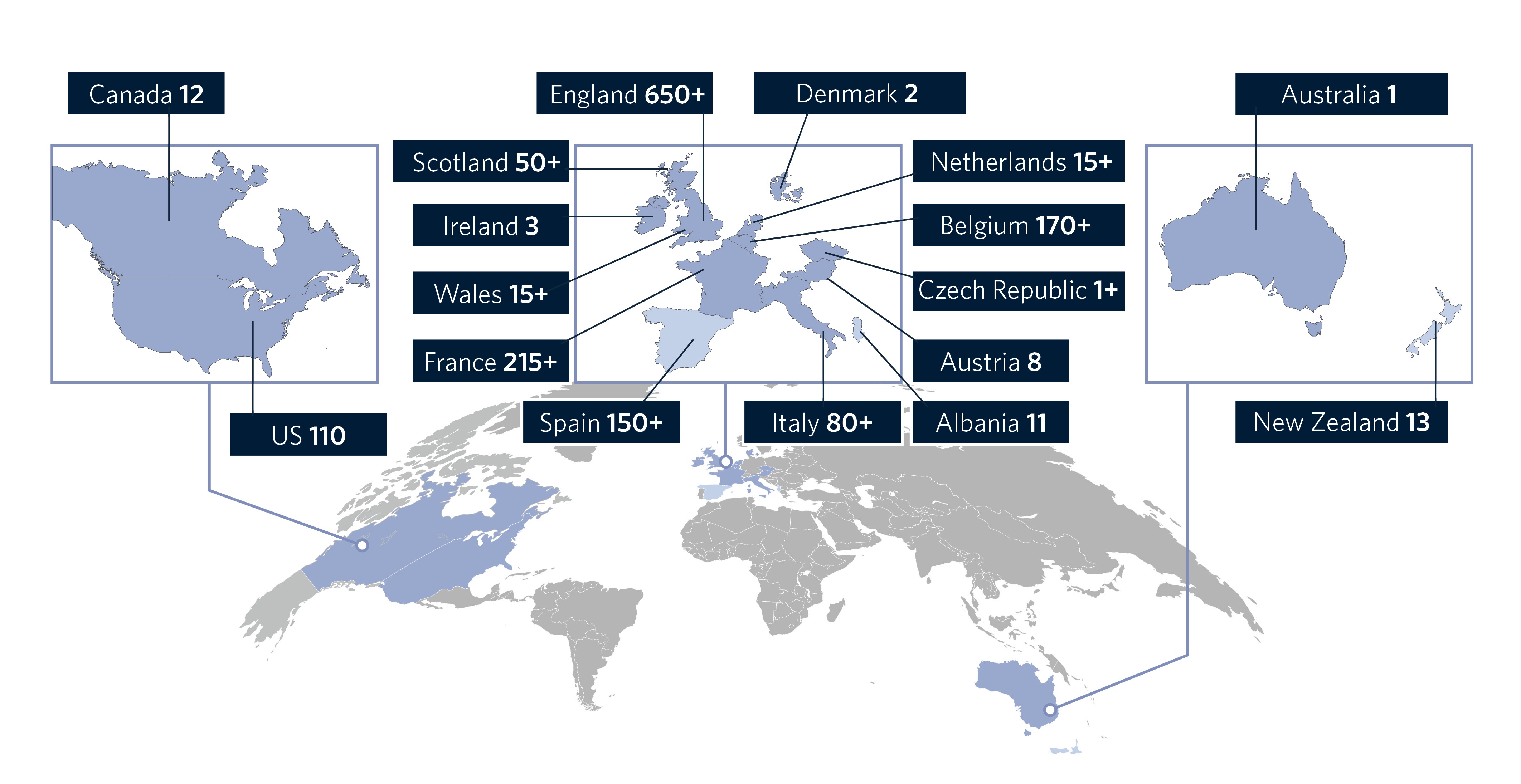

From just a handful of examples a decade ago, there are now well over 1,000 school streets in more than a dozen countries. Faced with the challenge of limited public transport capacity and the need for additional space for social distancing in response to COVID-19, many cities responded by fundamentally changing the way that street space was allocated.

London, Paris, New York and Milan all took steps to ban vehicles from the roads outside schools. In doing so, they also drew on, and added to, evidence that school streets reduce the risk of road traffic injury, improve air quality and support active travel – creating positive changes to make streets safer and healthier for children.

A recent report by the Child Health Initiative (CHI) School streets: putting children and the planet first tracks this growth for the first time – including a five-fold increase between 2019 and 2021. The report takes a political economy approach to understand the factors that influenced this rapid change, analysing the ideas, institutions and incentives that made this expansion possible.

So far, car-free school streets have mainly been tried in high-income contexts. But school zones that aim to improve road safety, such as this one in Mumbai, are also increasingly being implemented in Africa, Asia and Latin America. The report aims to share practical lessons and resources about car-free school streets for others to draw on and adapt to their own circumstances.

School streets around the world. © FIA Foundation / Child Health Initiative

The rapid increase in numbers of school streets highlights four key lessons for urban transformations for children – around priorities, adaptive approaches and learning, leadership, and breadth of vision. Each of these lessons is expanded upon and explained by two further principles and by examples and experiences from the growth of school streets.

1. Have positive priorities

Put children first: Evidence from around the world suggests that a large proportion of child road-traffic injuries occur near schools: in Chile, 95% are within 500m of a school.

[bctt tweet=”School streets provide opportunities for safe and active travel, social connections and play. Ultimately, this means designing streets with children in mind, rather than prioritising cars” username=”cities4children”]– the Global Designing Cities Initiative’s Designing Streets for Kids guide provides a range of examples of how this can be done.

Make life better: Car-free streets reduce noise, stress, pollution and the risk of injury. Evaluations show a measurable positive impact, such as reducing air pollution around schools by almost a quarter in London, and increasing levels of physical activity. They are also overwhelmingly popular with parents, teachers and pupils.

The street experience is more enjoyable and promotes health and well-being while also taking action on climate change. The range of benefits makes the case for school streets compelling and helps bring together different stakeholders and campaigners in support.

A car-free school zone in The Hague © City of The Hague

2. Pilot new approaches and share experiences

Simple ideas can be easily replicated: School streets are a simple idea that is relatively low-cost to try. Taking an experimental approach – sometimes called ‘tactical urbanism’ – allows for radical changes to be experienced and evaluated. Temporary timed street closures can be trialled with basic materials, such as standard temporary barriers.

Some school streets use technology (automatic enforcement using vehicle number plate recognition cameras) to reduce the numbers of regular volunteers required. This adds up-front costs but lowers the ongoing organisational burden.

Learn from others and adapt to local contexts: One of the key drivers of the expansion of school streets has been the number of organisations taking time to share learning and disseminate it for others to draw on, including producing toolkits and sharing practical experience. This includes the London Borough of Hackney’s toolkit for professionals, as well as others from Belgium, Canada, and the USA, which have inspired others to try the school streets idea.

Although many of the examples have been in Europe and North America, the low costs involved mean there is also the potential to experiment with the concept in Latin America, Asia and Africa and share learning between these contexts. School streets work best on lower-volume streets, including in areas where speed reductions, such as 20mph or 30kmh zones have already been introduced. Alternative safety measures and physical design changes need to be made on high-volume streets.

3. Be ambitious

Seize the moment: [bctt tweet=”School streets can be seen as an idea whose time has come. From very low numbers in less than a handful of countries in 2012, a decade later there are over a thousand across more than a dozen countries.” username=”cities4children”] The COVID-19 pandemic provided a necessity for action – and many cities were motivated to ‘build back better’ by expanding school streets to create additional space outside schools for social distancing, as well as safe routes for walking and cycling.

Leaders in many cities and local authorities have stepped up to make a difference and reimagine a better future. Some cities had already initiated school street projects, which they were able to significantly scale up or expand, while others drew on the experiences of other cities to implement them for the first time. Implementing new school streets in countries or cities that have not done them before may mean creating new processes or adapting existing ones, and supportive and engaged local politicians can be crucial in approving the relevant paperwork and bringing the right stakeholders together to reach agreement.

Alderman for Mobility, Robert van Asten promoting school streets in the Hague © City of The Hague

Build on momentum and institutionalise change: The growing evidence for the benefits of car-free school streets has created a momentum that others can emulate. There are a range of organisations who can share experiences and help work through practicalities.

For cities that have trialled school streets, the next stage is to make them permanent. Initially, temporary school streets can be implemented by using low-cost materials, but over time budgets can be allocated for permanent transformations and landscaping, such as has been introduced in Paris. While many cities have opted for timed traffic restrictions, some cities, such as Barcelona and Tirana have instead implemented physical changes to road layouts (such as removing a lane of traffic) to limit the space that vehicles can use and transform the street into an ongoing space for people.

Transformation of street space in Tirana, Albania to create more space for children using concrete bollards to mark a wider pedestrian area protected from vehicles © Qendra Marrëdhënie

4. Take a citywide approach

Invest in proven road infrastructure measures: School streets can make the area around schools safer for walking and cycling, but they are most effective when they are part of a comprehensive active travel network. In terms of city design, there is strong evidence about what works, including safe cycle lanes, pavements and crossings, and low speeds where people and vehicles interact. The World Health Organization calls these Streets for Life.

During the pandemic, many cities took a comprehensive approach and simultaneously introduced a range of measures, which unlocked wider benefits. Whether in Bogota, Fortaleza, New York or Paris, cities that have taken a comprehensive approach have reduced injuries, encouraged a shift to active travel, and made their cities more liveable for everyone.

Measure air pollution from vehicles: One of the reasons that the idea of school streets exploded in Europe was because of a growing awareness of the impact of air pollution on children’s health over many years. This was in part due to increased testing of vehicles and collection of data. We know that air pollution is worse in many developing countries, but a lack of relevant data inhibits creating awareness. Testing air pollution around schools, such as in the TRUE emissions initiative, helps inform action and catalyse broader campaigns.

TRUE emissions testing in Mexico © SEDEMA (Secretaría del Medio Ambiente)

Next steps for school streets

Ensuring the area outside schools is safe and welcoming is vital as the journey to and from school is undertaken by around 1 billion children each day.

So far, most school streets been in high-income countries. But the low costs and simple concept potentially make them transferable to other settings. Regulations differ by country and urban authority, so often the first step is to work out the paperwork required to temporarily close a street, and work with local stakeholders to pilot a temporary closure. Over time, steps can be taken to simplify this process to enable a wider scaling up. Cities that have already piloted or established car-free days may be well placed to trial school streets if the relevant processes are already in place.

There are already inspiring examples of organisations making changes to reduce road safety risks around schools in these countries, such as Amend’s School Area Road Safety Assessments and Improvements (SARSAI) programme, which won the inaugural World Resources Institute Ross Prize for Cities, as well as car-free ‘open-streets’ movements. Low speed limits, such as 30kmh or 20mph zones, are a key building block of safe urban mobility.

Can school streets also improve life in these cities? The evidence suggests they could – but it may take determined leadership and collaboration between a range of local stakeholders to try something new and secure the multiple benefits that school streets bring.

For many cities around the world, of course, the priority may be getting the basics of safe streets in place, such as low vehicle speeds and safe crossings wherever pedestrians and vehicles mix – but there may also be a role for school streets that remove vehicles completely.

About the Author

Richard Clarke is Policy and Evidence Manager at the FIA Foundation, which hosts the Child Health Initiative. His work supports the Foundation’s global advocacy work around safe, clean, fair and green mobility for all, including road safety, active travel, the transition to zero emission vehicles and liveable streets. The Child Health Initiative aims to enable a safe and healthy journey to school for every child by 2030, in line with commitments made in Sustainable Development Goals and Habitat III New Urban Agenda.

The Ideas4Action series aims to inspire with ideas that have worked in other cities and countries so that you too, can take action in your own city. Read more of our blogs here.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. When re-sharing this content please ensure accreditation by adding the following sentence: ‘This blog was first published by the Global Alliance – Cities4Children (www.cities4children.org/blog)’