Author: Cities4Children

ITDP’s new report, 15-Minute-Neighbourhoods: Access and Babies, Toddlers and Their Caregivers, has been released, and this webinar discussed how this can contribute to urban wellbeing. The conversation was moderated by Ankita Chakra, Knowledge for Policy Director at the Bernard van Leer Foundation. The panelists included Aimee Gaulthier, Chief Knowledge Officer at ITDP, Iwona Alfred, Program Manager, Content Management and Production, ITDP Global, Santiago Fernandez Reyez, Urban Development and Research Manager, ITDP Mexico, and Anuela Ristani, Deputy Mayor of Tirana.

Understanding what ‘having access’ means in a city, is an important starting point. Gaulthier says it’s imperative that we understand whether people have access to destinations by using public transport or on foot, and if not, what can we do about it? She reflects on how traditional transit has been developed around the able-bodied male commuter, often leaving caregivers and children on the backfoot. In many cities, especially those dominated by cars, pavements tend to be an afterthought, often poorly kept, uneven, and close to polluted roads, which are not ideal for parents trying to navigate the city with pushchairs or young children.

With these issues in mind, ITDP worked together with the Bernard Van Leer Foundation to produce a report on the unique mobility characteristics of caregivers, babies, and toddlers in the city looking at:

- Where do young children and their caregivers need to travel to?

- Are there adequate public spaces available where caregivers can give love and time to children?

Researchers found that by walking and cycling, caregivers can provide care more easily: they have more opportunity for interaction, more physical activity, and an improved social connection.

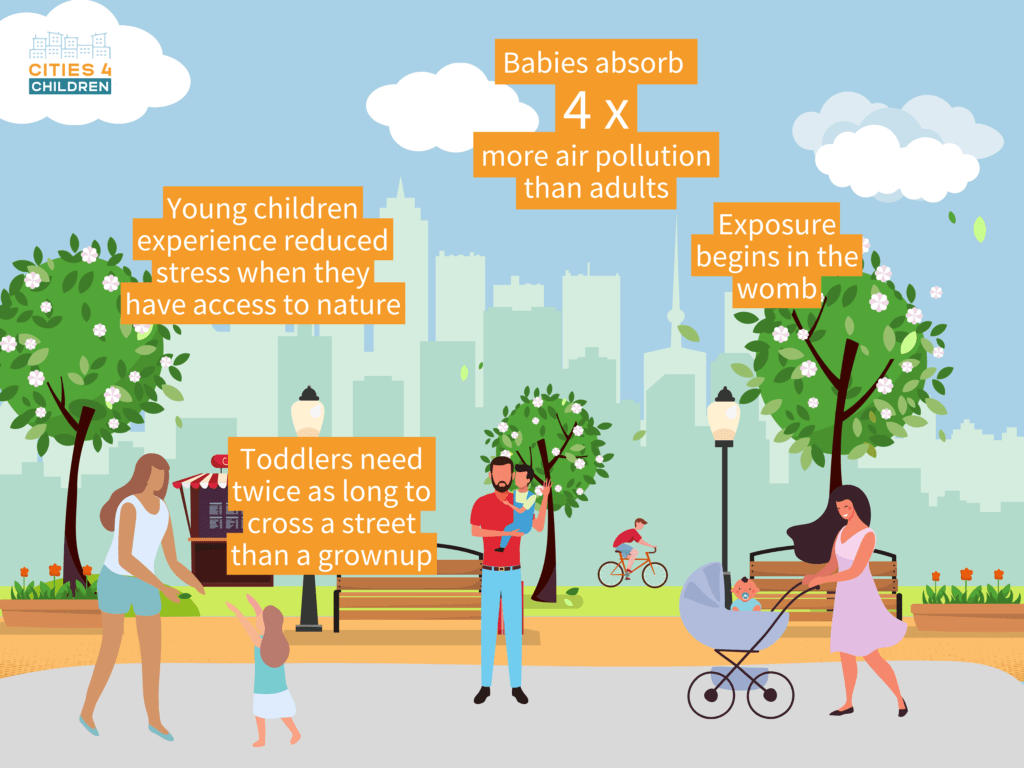

The report highlights needs and issues concerning children: babies absorb four times more air pollution than adults, and exposure begins in the womb; toddlers need twice as long to cross a street than a grownup, and young children experience reduced stress when they have access to nature.

What parts of urban design do we need to have a workable 15-minute-city?

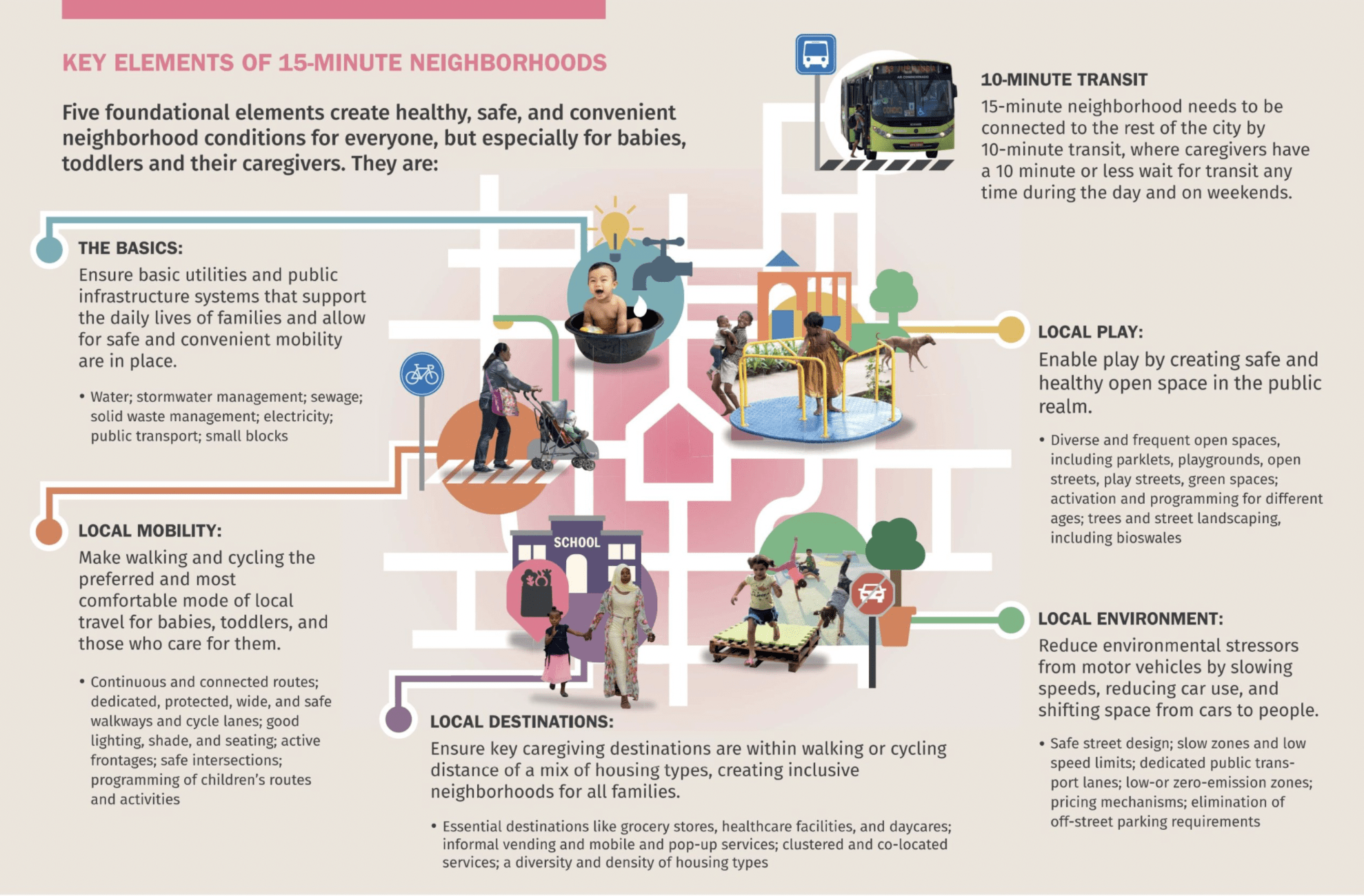

Public space, including streets, parks, pavements, that are comfortable, safe and accessible, are vital for children and their caregivers. The Urban95 initiative encourages partners to work on diverse parts of city design, including improving mobility by creating safe and convenient ways for caregivers and small children to reach their destinations.

The 15-Minute-Neighbourood concept is one of the two core recommendations in the report. Walking is a critical form of mobility, and it’s hard to access services if you must travel far on foot. Caregivers have clear mobility habits, including trip chaining (when multiple chores need to be conducted on one trip), off-peak travel, and multiple, shorter trips on a regular basis to access key services.

Benefits of the 15-minute city

We must consider how long it takes people to access services to best understand the city. In 15-minutes, a caregiver with a small child can walk 240 metres. In the same amount of time, a grown adult male can cover one kilometre, says the report. Everyone is served by the 15-minute city. It enables chain-linking mobility, allows basic infrastructure to thrive, and provides space for connected mobility networks.

The 15-minute-city also encourages investments in local destinations. Essential services such as doctor’s surgeries and schools should be 15 minutes from home, while shops and pop-up services can be a way of getting around limits, around prohibitive cost or availability of permanent service provision.

Children learn and develop through play. When it comes to providing more than mobility, actual fun for children and young people in the form of parks and spaces to play, variety is key. Spaces should include natural spaces, diverse and nearby spots to play in, as well as activation and programming for all ages. These offerings are critical for healthy cognitive and physical growth.

“It’s about more than just access. It’s about human rights,” says Anuela Ristani, deputy mayor of Tirana, Albania. “Giving people the opportunity to fully access their city is so fundamental, it’s not a civic duty, or a first world problem, it’s a basic human right. We must have access to these basic services, independent of gender or race. We’ve failed at this. We’ve long-given priority to those who have the means, who live in wealthier areas. We have failed to understand that the same need is for everybody. The job of the city is to invest in basic infrastructure for all, to provide safe services and access to services for all.”

Source: ’15-Minute Neighborhoods: Meeting the Needs of Babies, Toddlers, and Caregivers’ (2022); Bernard Van Leer Foundation and ITDP.

How to achieve a 15-minute city?

If the concept of a 15-minute-city sounds too good to be true, it doesn’t have to be. The report goes into depth around how best to kickstart the process.

“In Tirana, we’ve invested in local infrastructure by teaching our kids how to cycle from the age of three in kindergartens. That way they can make the most of the city services. It teaches kids about independence and how to be a full citizen, giving children full access to the city,” adds Ristani. “To make a 15-minute-city successful, we also need to crush the idea that having a car gives you special access. It does not make you more worthy, and we need to put the spotlight back on other city users.”

Tirana has also introduced a ‘streets for kids’ initiative: the objective is to make a safe space around school buildings for children living close by. This means you close the streets around the schools for the majority of the time. “We found out that traffic is mostly generated by parents driving their kids, and often from close by. They’re driving because they don’t feel safe. So we closed all space for cars, so parents don’t have to drive them or take them”.

Mangesh Dighe, explores some of the ways the city of Pune in India has opened up to children: “We’ve opened community gardens, which have had high levels of community participation, established a steering committee to drive discussions and initiatives, and began to develop networks with NGOs and local level organisations”.

Children’s mobility and understanding of the city can be brought to them by looking at things that are at their level, says Dighe. In Pune, they’ve introduced a traffic plaza, which has road signs stamped on the ground and on signs at child-height, curbs are lower, and sidewalks wider. “Everything is scaled down, and there are also outdoor games, transforming streets into children’s play areas”.

In short this webinar flags that the 15-minute-city can be made possible, especially if you want to develop an inclusive and accessible city for all ages.

Let us know – would the 15-minute model work for your city?

Listen to the full webinar for more information here and read the report by ITDP here

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. When re-sharing this content please ensure accreditation by adding the following sentence: ‘This blog was first published by the Global Alliance – Cities4Children (www.cities4children.org/blog)’