Author: Olivia Nielsen

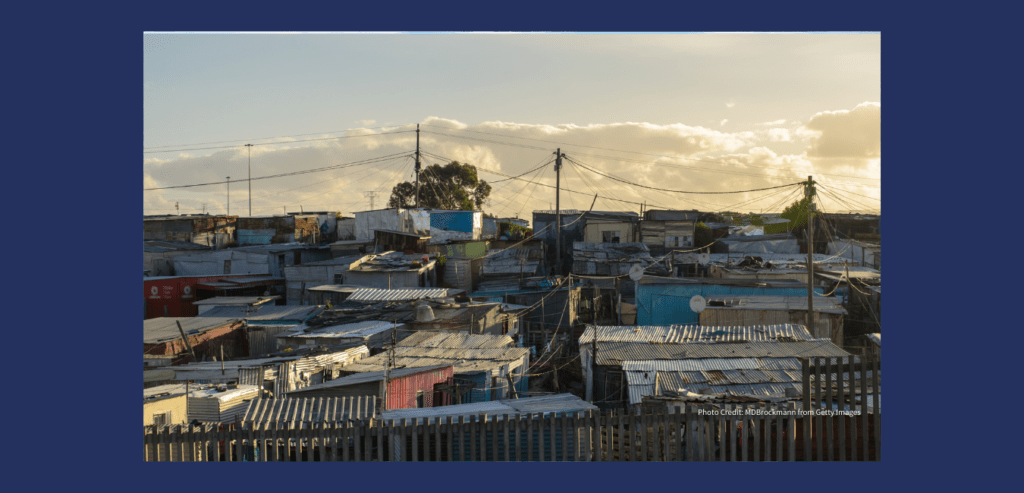

Poor-quality housing can be a matter of life and death, especially for children. Governments often focus on building new homes rather than improving the quality of existing ones. Yet the COVID-19 pandemic and ‘shelter-in-place’ orders have highlighted the importance of doing so. Here, Olivia Nielsen explores the dangers of sub-standard homes for young children and presents simple solutions to overcome them and save lives.

Why improve the quality of existing homes?

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced many of us to re-evaluate the adequacy of our homes. With most schools and many places of work shut, parents around the world have been juggling the difficult task of working from home with their children in the same confined space. As a mother of two young girls under two, I have become all too aware of the numerous difficulties of doing so. But I am fortunate enough to live in a safe home, which is not the case for over 440 million households worldwide who live in precarious homes often lacking a resilient structure and access to key utilities such as water, energy and sanitation.[i]

In most developing countries, two out of three families simply need a better home, not a new one.[ii] As an advocate for safe, resilient and affordable housing worldwide, I thought it important to show that we must invest in upgrading existing homes. [bctt tweet=”Here, I consider some simple incremental upgrades to poor-quality housing that could improve the safety of homes for children and improve their quality of life, health, education and well-being.” username=”cities4children”]

But although these upgrades may sound simple to introduce at the individual household level, they will require government interventions to be addressed at scale. The COVID-19 pandemic has shown the need for governments to urgently invest in better housing as a matter of public health but also to protect the next generation. It influences children’s physical and educational development and can have long-term health impacts. What can cities do to improve housing conditions and build healthier communities for all?[iii] Here I consider some ideas on:

- Supporting home improvements to achieve better health outcomes

- Making existing homes stronger and more resilient, and

- Upgrading neighbourhoods to make cities better for all.

Supporting home improvements to achieve better health outcomes

Replacing dirt floors

Today, over a billion people around the world still live on dirt floors.[iv] This poses significant health risks for children. Yet there is a simple and effective remedy. Replacing a dirt floor with a cement one can significantly improve the physical and cognitive development of children. A World Bank study in Mexico showed that a complete substitution of dirt floors by cement floors in a house leads to significant reductions in parasitic infestations, diarrhoea and anaemia as well as improvements in cognitive development. For children, a simple change in flooring can be a matter of life and death.

This may be easier said than done. Replacing dirt floors can cost hundreds if not thousands of dollars and would be too expensive to implement for many households. Instead of placing the financial burden on the family, I encourage governments to commit their budgets not only to new housing construction but also to home improvements, an area often overlooked.

Cleaner cooking

Poor-quality housing can be a cause of many other concerns for young children. For example, open-fire cooking remains a major issue worldwide. According to the World Health Organization, around 3 billion people still cook using open fires or simple stoves fuelled by kerosene, biomass (wood, animal dung and crop waste) and coal.[v] Around 4 million people die every year prematurely due to indoor air pollution caused by these cooking practices. Young children are particularly at risk and can suffer from acute pneumonia. Though underreported, the physical dangers of having young children around open fires can only be imagined.

Fortunately, clean cook stoves are relatively affordable and accessible. Many programmes have been implemented to increase their use and availability with the hope of making safe cooking available to all. China experienced great success in doing so and distributed over 180 million clean stoves in a decade.[vi] However, other countries have seen slower results as they have placed the financial burden on the household itself. We must continue to push these efforts and eradicate diseases caused by open-fire cooking.

Simple structural retrofits: making buildings stronger and more resilient

When children cannot easily leave their homes during a disaster, we need to ensure that their homes are as safe as possible. Every year 175 million children around the word are affected by natural hazards and climate-related disasters, which effect their physical, mental and educational development.[vii] Homes need to be safer to save lives, avoid displacement and promote educational development.

Simple and cheap structural retrofits can make a big difference in mitigating hazards and saving children’s lives by reducing risk of collapse during an earthquake or hurricane, such as adding a continuous ring beam, additional interior partition walls or reinforced concrete slabs between floors.[viii] The World Bank is currently working with governments in Latin America to strengthen existing homes before the next disaster strikes.[ix]

New technologies are also seeking to identify homes at risk and implement retrofits before it is too late. For example, in hurricane-prone Saint Lucia, a geospatial housing inventory was taken of over 10,000 buildings using drones and machine learning. The inventory was then used to estimate potential housing damage and losses from a Category-5 hurricane.[x] Generating household-level information like this could provide governments, homeowners and others with the baseline data needed to mitigate damage from future natural hazards and climate-related disasters.

Upgrading neighbourhoods to make cities better for all

Beyond these life-saving housing upgrades, simple solutions can also increase the quality of life of children around the world. Today, two-thirds of school-aged or 1.3 billion children around the world still do not have access to the internet at home[xi] and may face learning delays during the pandemic’s school closures. From better lighting to access to the internet, school-aged children need tools to study at home – especially when schools, libraries and public spaces are closed due to the pandemic. When cities invest in slum upgrading projects or when governments launch large infrastructure development programmes, they shouldn’t leave behind the utilities that may help educate a whole new education.

What can policymakers do?

The pandemic has only made the need for child-safe housing ever more urgent. For millions of people worldwide, creating a more child-friendly home will involve important life-saving – though not necessarily expensive – retrofits. These can go a long way in improving the lives of children and their families. As affordable and simple solutions abound, we can no longer accept that children grow up in houses that are physically dangerous to their development.

To make this happen, policymakers need to commit their budgets not only to support the construction of new homes, but also repair, strengthen and upgrade existing ones. To do so, the qualitative housing deficit needs to be estimated and understood as housing deficiencies may vary from one area to the next. With this data in hand, governments can develop national and/or local programmes to tackle specific issues. As climate change will only increase the risks poor-quality houses are exposed to, the need to act has become urgent.

A child stands outside a post-disaster home in Latin America © Miyamoto International

About the author

Olivia Nielsen is an Associate Principal at Miyamoto International where she focuses on resilient housing solutions. From post-disaster Haiti to Papua New Guinea, she has developed and worked on critical housing programmes in over 30 countries. Olivia has a decade of experience in housing finance, housing public-private partnerships, post-disaster reconstruction and green construction. Through her work she hopes to make safe and affordable housing available to all.

Endnotes

[i] McKinsey Global Institute (2014) A blueprint for addressing the global affordable housing challenge. https://mck.co/3znwdWz

[ii] Libertun de Duren, NR (2018) Why there? Developers’ rationale for building social housing in the urban periphery in Latin America. Cities 72(B): 411–420. https://bit.ly/3nQpp1O

[iii] See also Trivenoolivia, L and Nielsen, O (18 March 2020) Home sane home. World Bank Sustainable Cities blog. https://bit.ly/39sMzD0

[iv] University of Oxford (22 June 2015) Latest figures on where 1.6 billion poor people live. https://bit.ly/3tXkwop

[v] WHO (8 May 2018) Household air pollution and health. https://bit.ly/3hMfOoY

[vi] World Bank (2013) China – accelerating household access to clean cooking and heating (English). https://bit.ly/3CoAfzS

[vii] Coley, RL (ed.) (2020) Understanding the impacts of natural disasters on children. Society for Research in Child Development. https://bit.ly/3CINJXJ

[viii] Elizabeth, S and Triveno, A (16 November 2018) Resilient housing joins the machine learning revolution. World Bank Blogs: Sustainable Cities. https://bit.ly/373swtw

[ix] World Bank (2019) Global program for resilient housing. https://bit.ly/3zpTc3m

[x] Elizabeth, S and Triveno, A (16 November 2018) Resilient housing joins the machine learning revolution. World Bank Blogs: Sustainable Cities. https://bit.ly/373swtw

[xi] Buechner, M (2 December 2020) Two-thirds of world’s school-age children have no internet at home. Unicef USA. https://bit.ly/39kNC7I

Note: This article presents the views of the author featured and does not necessarily represent the views of Global Alliance – Cities 4 Children as a whole

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.