Author: Marta Briones

The Covid-19 pandemic brought urban life to a halt and turned children’s lives upside-down overnight. Across the world, children no longer had lessons or physical contact with their friends, and could not play or exercise outdoor. Strict lockdowns and mobility restrictions have shown the importance of more and better public spaces in our cities.

Nearly two years on from the outbreak of the pandemic, it’s time to rebuild and rethink cities. Given that one third of the 4 billion people who live in urban areas are children, it is clear that a successful city transformation process must be carried out with children in mind. This is not only because children’s opinions and needs are important, but because they will inherit the cities we build today.

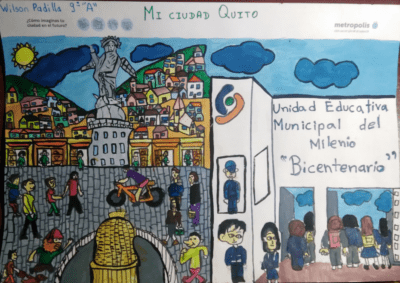

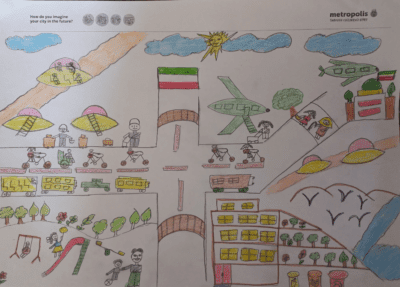

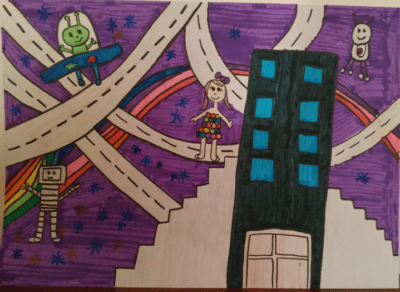

The Metropolis Through Children’s Eyes initiative was launched by Metropolis, World Association of the Major Metropolises, to convey children’s opinions, experiences and suggestions – expressed through drawings – to local and regional governments across their network. Over 1,200 children between 5 and 14 years old from more than 33 cities called for their needs to be considered when designing urban spaces. The results show how children imagine cities free of pollution and danger, where technology and nature help us to provide opportunities for everyone.

Another use for public space: socialising and play

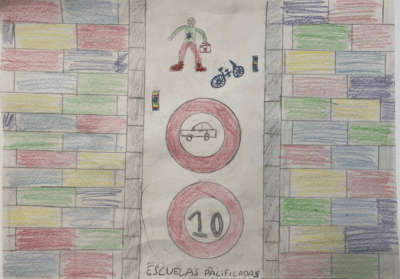

Giving priority to cars limits children’s mobility and autonomy and restricts their opportunities for play, while reducing children’s safety and increasing road and traffic accidents.

For children who live in cities, schools and other social spaces can provide their first introduction to nature, social interaction, physical activity and play.

One good example of inclusive public space is turning the areas surrounding schools into safe, noise and pollution-free areas, as well as implementing measures to deter or prevent parking at school entrances, in order to protect children.

Safer and more inclusive cities

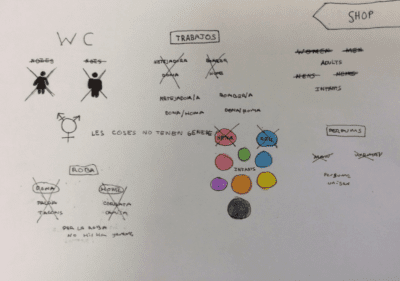

The gender gap manifests itself in a number of ways, including sexual harassment in public space, or a lack of gender perspective in mobility planning. Children imagine safe and inclusive cities where all people live, work and participate in urban life without fear of violence and intimidation.

“A walk without any fear or risk…” – Erika Lizbeth Lapo Jaramillo, 12 years

This goal is part of a gendered approach to urban planning that incorporates the visions, needs and problems of the entire population equally. As Plan International reminds us, the needs of girls are all too often blurred with those of “all children” or “women and girls”. Applying a gender perspective to urban planning is important to combat the inequality that can cause violence.

Promoting active and sustainable mobility

Children look to the urban mobility of the future, in which the use of the car is overshadowed or cancelled out by aeroplanes and drones. Urban mobility is likely to be more sustainable thanks to electric motors that facilitate a zero-carbon footprint, while covering greater distances and flying between urban centres.

The current transport model in large cities needs to incorporate children’s daily lives, needs and expectations, because this is the only way we can guarantee that all citizens are provided for.

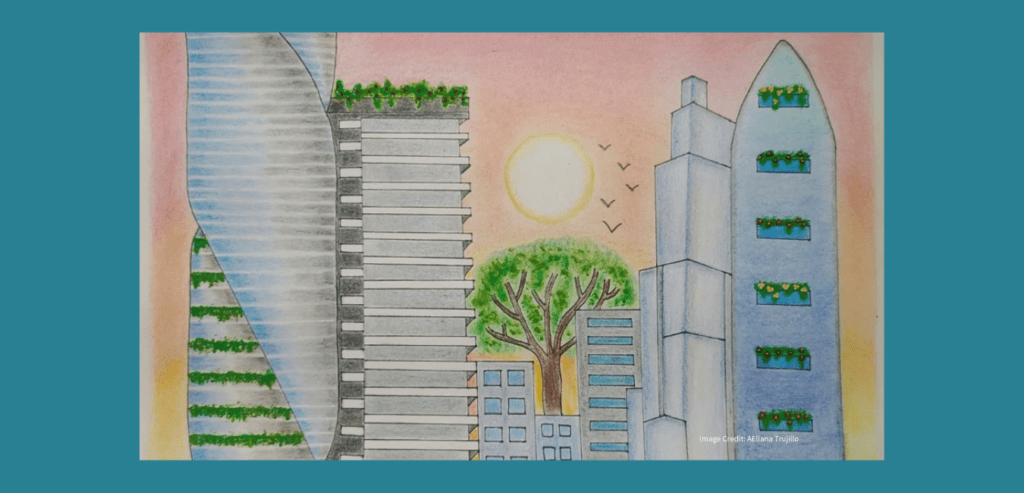

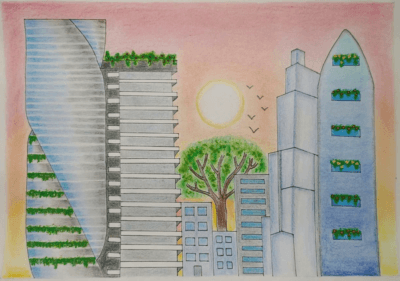

Increasing urban green spaces

Renaturalising the city has widespread benefits for mitigating the impact of the climate emergency on health. Studies of children have shown positive links between greener environments and improved attention span, emotional and behavioural development, and even positive structural changes in the brain. Tall buildings now compete with leafy trees. For children, the sea takes centre stage in their imaginary city of the future.

It is essential to listen to and respond to children’s perspectives on climate change. Failure to do so would not only undermine their right to be heard and to participate, but also hinders the effectiveness, strength and power of policies and the response to climate change itself.

In short, the social and health problems left in the wake of the pandemic will shape a future of city transformation in which children’s perspectives must be accepted across urban policymaking processes.

Just like any crisis, the pandemic can act as a lesson for how to be responsive and resilient in an environmental emergency. If we can interpret the responses from children and young people, we’ll be able to help locate the necessary tools to respond in a timely manner to this climate emergency—one that threatens our survival as a species.

About the Author

Marta Briones is a journalist specialised in International Relations.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.